November 3, 2016

Research From Penn Prof. Michael Leja Explores the Art of Elections

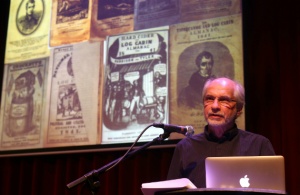

Michael Leja, a history of art professor and chair of the history of art graduate group at the University of Pennsylvania says today’s standard of hyper-mediatized presidential campaigns started with the United States presidential election of 1840, the first in which images played a significant role.

Leja studies the visual arts in various media, including painting, sculpture, film, photography, prints and illustrations, from the 19th and 20th centuries.

His work focuses on understanding art in relation to contemporary cultural, social, political and intellectual developments. It also examines the nation’s presidential past through visual artifacts, including the image campaign of 1840 that introduced the use of lithographs, wood engravings and other eye-catching elements.

Even without mass media as we know it today, Leja says that once people realized the political power of pictures back in 1840, presidential campaigns have not been the same since.

In that year, the Whig party mobilized a mass following for its candidate, William Henry Harrison, including the widespread production of images, which were widely distributed and created an image for Harrison through words and pictures.

“Pictures served to fabricate an attractive persona for Harrison,” Leja says, “and the party used the developing mass media to make a cult figure of the candidate.”

Images of Harrison heroically leading soldiers into battle, negotiating with Native-American leaders and welcoming visitors to his log cabin flooded the print media. They also made their way onto dishes, teapots, lapel buttons and handkerchiefs.

But the central motif of the 1840 campaign featured a log cabin, next to a wood pile and a cider barrel. This image sometimes included patriotic fixtures, such as flags and eagles.

There are two sides of the story as to why the images included a log cabin, Leja says.

The first side of the story is that in an effort to ridicule Harrison, a newspaper reporter for the Baltimore Republican wrote that if the Whig candidate were given an annual pension of $2,000 and a barrel of cider, Harrison would be content to spend the rest of his life in his log cabin studying moral philosophy, meaning in essence, he’d do nothing. But, the Whig party hijacked this idea and it yielded a feisty and enthusiastic response from voters.

“Although he was a college-educated Virginia aristocrat whose father was a signer of the Declaration of Independence, the emblem turned Harrison into an unpretentious neighborly farmer with humble log-cabin origins,” Leja says. But, the party’s use of log cabin images did much more.

For many reasons, the log cabin symbol was an enormously successful device for generating a sense of togetherness among those who counted themselves as Whigs.

Log cabins brought together people from all walks of life: the defenders of the western frontiers, residents of western states who were born in log cabins and early settlers began to see Harrison as an associate. They also aligned Harrison with former presidents like George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson.

Most importantly, these images generated a sense of affiliation, charm and nostalgia, awakening enthusiasm for Harrison and the log cabin was an effective stimulus to collective fantasy and memory, says Leja. “The cabin image tapped into a wellspring of national and personal pride. It reminded viewers of a shared past experience that bound them to one another and the fictional Harrison image that’s associated with the log cabin.”

But, for many Harrison supporters, he says, the second side of the story is that the log cabins represented the campaign’s cleverness.

“The Whigs eagerly credited the Democrats with making the connection to the log cabin,” says Lejay. “Turning the tables on the Democrats meant transforming the association of Harrison with a log cabin from a Democrat’s demeaning fantasy to the Whigs’ heroic populism.”

He says this was the first instance of a political campaign using pictures on a mass scale.

“The log cabin represented what was claimed to be an essential fact of his identity – Harrison was a log cabin dweller,” says Leja. “But, for those who knew the origin story, it stood for the shrewd cheekiness of the Whig campaign.”

Lithographs of log cabins were sent all over the country for free, and almanacs, a popular publication of the time, exploded with Harrison imagery in 1840. The campaign had a substantial impact on voters in rural audiences says Leja.

“From the beginning, pictures emblematic of a personal history or a character trait alleged to epitomize a particular candidate became a core form of political rhetoric,” Leja says. “The insistent repetition of the log cabin image in the Harrison campaign is a classic case of branding Avant La Lettre.” In other words, it was branding – long before there was such a thing as branding.

“The log cabin became identified with Harrison at a level that transcended truth,” Leja says.

Later in the campaign, images published in almanacs and oversized posters tacked up in public spaces portrayed Harrison as a heroic leader and a statesman, while other pictures symbolized his bravery and military prowess. Certain images depicted him as the kind of leader that would not eat on the battlefield until all of his troops had been fed. Others illustrated his humanity during times of military escalation, such as instructing soldiers to spare women and children and giving a blanket to a prisoner-of-war.

Throughout the campaign, says Leja, images were also designed to promote Harrison’s high principles and generosity, including him giving a horse to a minister, pardoning an assassin and being kind to an Irish immigrant who was on the low end of the social hierarchy at the time. This was designed to counter the image of Whigs being viewed as selfish aristocrats.

Referring to today’s political environment, the lesson, says Leja, is that 1840 was no less innocent a time in American politics.

That lesson resonated with the audience when Leja presented “Presidential Politics: The Image Campaign of 1840” on Oct. 18 at the monthly Penn Lightbulb Café. Among the audience was a group of 20 sophomores and juniors from St. Joseph’s Preparatory School, along with their American Government teacher, 1984 Penn alumnus William Conners, who has brought his students to Cafés for a few years.

Conners says later, the students discussed the influence that the 1840 campaign has had on other campaigns throughout history. Most importantly, he says, they also recognized the value of true scholarship.

“For example, a student did some online research after the Café to learn more about the use of images by the Whigs, but he told me that there was little available online,” says Conners. “His online search led him to appreciate the considerable amount of archival research Professor Leja must have conducted to prepare his slide presentation. For a high school history teacher, this is gold!”

https://news.upenn.edu/news/research-penn-prof-michael-leja-explores-art-elections