Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, associate professor of history of art, was the curator of the exhibition “Every Eye Is Upon Me: First Ladies of the United States” at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Portrait Gallery. Shaw returned to Penn this semester after taking an 18-month leave to serve as the Gallery’s senior historian and director of history, research, and scholarly programs.

March 2, 2021

First Ladies: As curator of an exhibition at the Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery, Penn's Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw tells the stories of the women who supported U.S. presidents while in the White House.

Louisa Shepard | March 1, 2021 | Penn Today

In a glass case in a Smithsonian Institution exhibition is a small cape, the ikat-dyed pink silk and fine black lace fanned out around a high collar in the center. The pleated taffeta fabric makes an almost perfect circle, except for an edge flipped over to reveal an interior inscription by the maker to the wearer.

The seamstress was Elizabeth Hobbs Keckley, a formerly enslaved woman, who stitched the capelet for first lady Mary Todd Lincoln as a gift in 1861, the year the two women met, and the first year of Abraham Lincoln’s presidency.

The friendship the capelet illustrates—between an African American dressmaker who bought her own freedom and the wife of a sitting president—is just the kind of personal story the curator, University of Pennsylvania’s Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, sought to highlight in the exhibition “Every Eye Is Upon Me: First Ladies of the United States” in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C.

During an 18-month leave from Penn, Shaw was the senior historian and director of history, research, and scholarly programs at the Portrait Gallery. In January she returned to her position as the Class of 1940 Bicentennial Term Associate Professor in Penn’s History of Art Department.

“It’s great to be permitted by the deans and provost to take that time to serve the country and be able to bring that experience back to Penn,” says Shaw who studies race, gender, sexuality, and class in American art. “My interest in being an art historian has always been about making the history of art accessible to students but also to the broader public.”

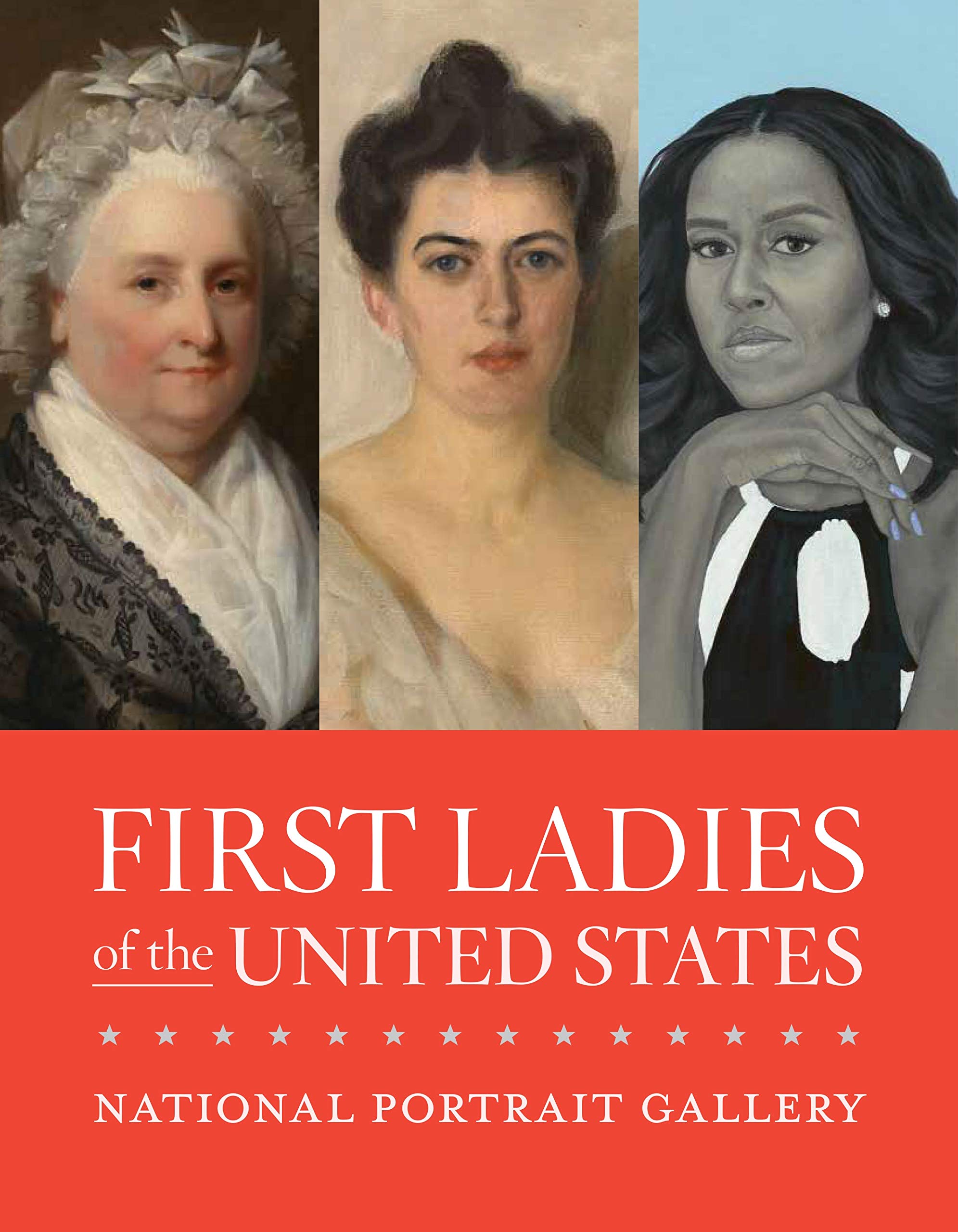

Shaw’s research and scholarship are woven throughout the exhibition on first ladies, which features 55 women in more than 60 works, spanning the more than 250 years from Martha Washington to Melania Trump. Described as the largest exhibition outside the White House on the portraiture of first ladies, the items include paintings, photographs, engravings, miniatures, sculptures, campaign buttons, and garments.

The Smithsonian closed just two weeks after the exhibition opened in November because of the pandemic; however, the works can be viewed online, and there is hope that the gallery will be able to reopen before the exhibition closes on May 23.

“The Portrait Gallery is both a history and an art museum,” says Shaw. “These portraits carry their histories.”

To tell the first ladies’ stories, Shaw considered how details of the women’s lives are woven into the history of the objects, as well as specific elements of the works, such as the frame, the setting, the background, her clothing, her hair, her relationship with the artist. “Why this image? Why this portrait? What aspects help in understanding that person’s life?” she asks. “I think about all of these elements and try to touch on these different aspects.”

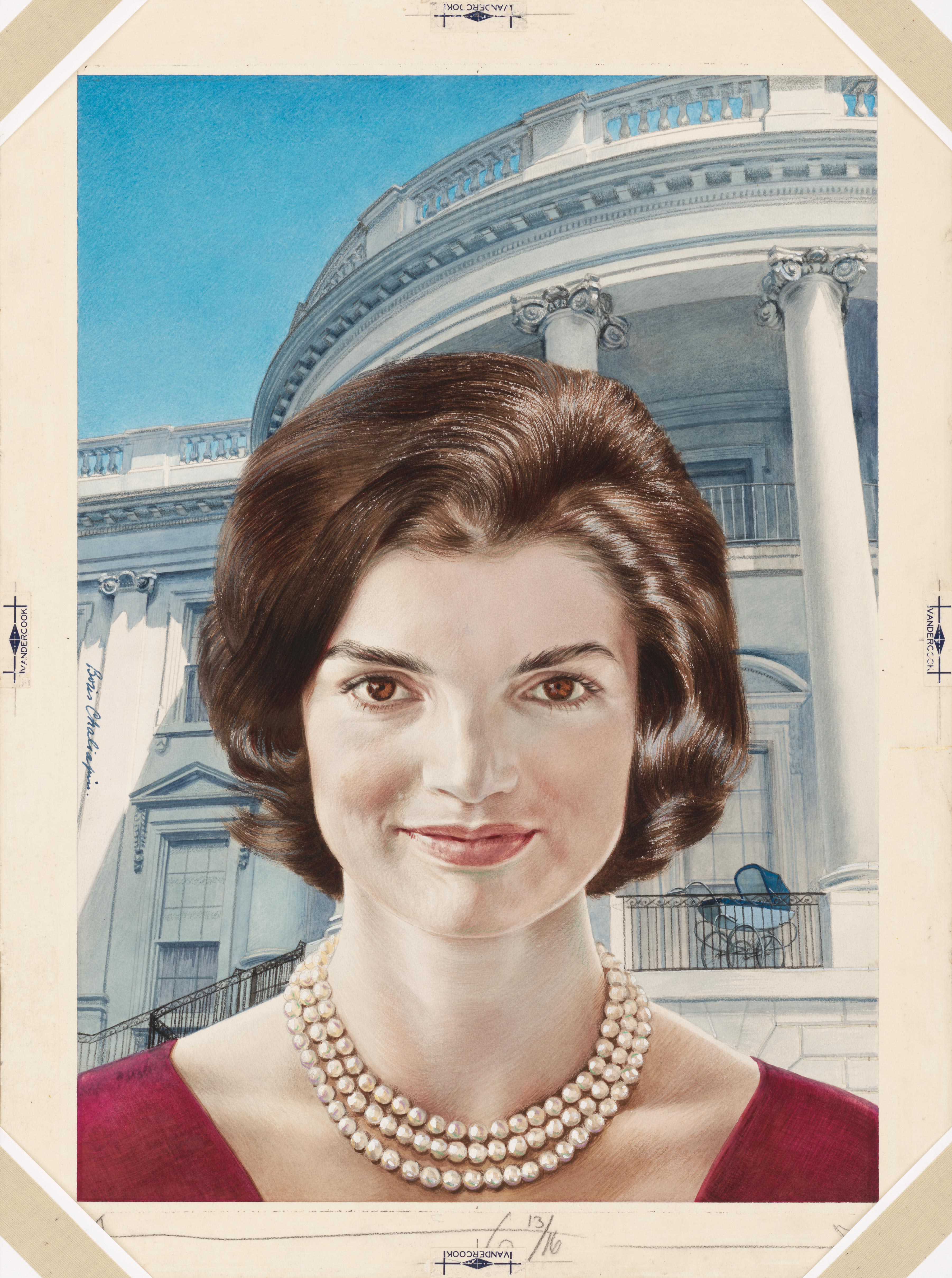

Shaw authored the accompanying 180-page book, “First Ladies of the United States,” meant as a companion to the National Portrait Gallery’s “America’s Presidents” volume, and she created a highlights audio and video tour. She worked with photographer Annie Liebovitz, who has taken portraits of every first lady starting with Jaqueline Kennedy, to create a slideshow of images in the gallery.

Shaw has given several virtual lectures, including one for the White House Historical Association, Penn Alumni’s Global Discovery Series, and a History of Art colloquium for Penn students and colleagues. And she has been featured in national and international news coverage of the exhibition, including The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, The Guardian, the BBC, Town & Country, the Daily Beast, and The Art Newspaper.

Now Shaw is bringing her D.C. experience into her classroom, teaching two seminars on contemporary art this semester. “Portraiture Now” includes a range of topics, from the portraiture of the past to portraiture in the social media memes of today, she says. The course is also examining the use of portraiture in the Black Lives Matter movement.

“It’s a way to bring a lot of what I’ve been thinking about while at the Portrait Gallery to my students, and focus on the renewal of interest in portraiture,” she says. “It’s a fun class that is very much tied to the contemporary moment, not just the contemporary art world.”

Michael Leja, History of Art Department chair, says many students plan to pursue careers in art museums as curators and educators. “Gwendolyn Shaw’s extensive work in these fields makes her an invaluable guide for our students,” he says. “Devising exhibitions that succeed in reaching a broad audience and enriching its understanding of art, history, and art history is challenging, and her record of success is remarkable.”

Shaw has been a guest curator for several museum exhibitions, including “Portraits of a People: Picturing African Americans in the Nineteenth Century” at the Addison Gallery of American Art, and “Represent: African American Art” at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. She has written several books and publications, including exhibition catalogs. For her Penn curatorial class she took students to Cuba to work with artist Roger Toledo to create a 2019 Arthur Ross Galleryexhibition.

In her National Portrait Gallery position, however, in addition to curating the First Ladies exhibition, Shaw oversaw the gallery’s curatorial and conservation departments, publications, and scholarly programs. When protests for social justice exploded in the spring after the murder of George Floyd, her focus shifted.

As monuments and memorials across the nation were taken down and destroyed, a social contract seemed to be broken, she says. “I began to be concerned about whether the shift would stop at the door to the museum when we reopened to the public,” she says. “I was concerned about the portraits of people whose legacies are being called into question.”

As a scholar she had considered depictions of historical figures in American art, like Andrew Jackson, but suddenly she was “in the position of being there to protect the works and to reinterpret these complicated individuals in the past,” she says. “The Portrait Gallery is not a hall of heroes. There are a lot of individuals with a lot of blood on their hands in those hallways. American history has a lot of violence embedded in it.”

Shaw and her team discussed which works should be put in storage or returned to their owners. They rewrote dozens of labels to reflect modern scholarship. “Ultimately, when we reopened we didn’t have any problems,” she says.

But the reexamination continued. She was involved in plans to renovate and reinterpret the pre-20th century galleries, which will include a new area on the post-Civil War era of Reconstruction.

“We’ve seen that kind of history is cyclical, and it repeats itself,” Shaw says. “And so it was really interesting for me to be a part of the museum in a year that included so much disruption to the status quo, that caused us to rethink, and reevaluate, the speed at which we needed to change.”

When Shaw took over as curator in 2019 the First Ladies exhibition was at that point a checklist. She had to locate and negotiate loans of the artworks, which came from several sources, including the White House, the State Department, the Library of Congress, presidential sites, libraries, and private collections. The Portrait Gallery only started commissioning official portraits of first ladies in 2006 with Hillary Rodham Clinton.

Shaw also delved into research to discover the personal stories of the women who supported presidents in the role of first lady. Most were wives, but for those presidents who were unmarried or widowed, the role of White House hostess went to sisters, daughters, nieces, or friends. It was necessary because any gathering with men and women in the 19th century required a hostess.

“It’s important to talk about women’s history and the ways that women were historically excluded from the written record as well as the visual record,” Shaw says. “We don’t have portraits of every first lady, even women married to these very powerful men. They weren’t considered important enough to be subjects of portraits.”

The National First Ladies Library in Canton, Ohio, was one of Shaw’s main research resources, as well as the White House Historical Association and American University’s First Ladies Initiative.

“I was really struck at how small that scholarly world is devoted to the history of first ladies,” says Shaw, especially compared with presidents, who have their own libraries, monuments, and historic sites. “There is something about studying the history of these women that removes partisan issues. They all suffer from joint obscurity in the official record.”

The exhibition explores how the women were portrayed and how they shaped the presentation of themselves during their days in the White House. “This is why portraiture is so important, because it tells us a lot about the ways that these women saw themselves, the ways that society valued them, and the period in which they lived,” Shaw says.

Many are portrayed only in photographs, including Mary Lincoln, as no verifiable painted portraits exist. There are no known portraits of any kind for a few. A rare marble bust depicts Harriet Lane Johnston, first lady for her bachelor uncle James Buchanan, which she commissioned herself.

Some of the mid-19th century portraits, however, are “glorious” Shaw says, portraying the first ladies almost as royalty. So large that it has often languished in storage, a full-length oil painting of Lucy Ware Webb Hayes, at more than 7 feet high, shows her dressed in an elaborate red velvet and lace gown.

“It’s great to bring them into the light,” Shaw says. “I was absolutely stunned at how grand they were.”

Shaw says she is often asked what first ladies think of their portraits. Barbara Bush, wife of George H.W. Bush, did not like her first official White House portrait. Son George W. Bush and his wife, Laura Bush, commissioned a new painting after the death of the first artist.

“It really shows the difference in how a portrait can present a figure like this to us,” Shaw says. “The first is more matronly and dowdy. It’s recognizable as Barbara Bush, but it does not have the same kind of presence and power and straightforward address as the one that was made subsequently.”

In the corners of the frame are little books, which reference Bush’s interest in literacy and writing. “This is one of the touches that I love,” Shaw says.

She took care to include several works of first ladies with their children. “The first lady really represents the first family,” she says.

Shaw’s opinions of some of the first ladies evolved as she researched their lives. “I developed a lot of retrospective affection for some of these women: Betty Ford, Nancy Reagan, Barbara Bush, Laura Bush, and Hillary Clinton, who I hadn’t seen as fully before. That was a real gift,” says Shaw.

“Being an Americanist and an art historian, to learn about it and study it and to see it in as robust and complicated a way as possible really helped me to expand my vision in ways I hadn’t expected.”

The title of the exhibition comes from a letter Julia Gardiner Tyler wrote to her mother soon after marrying John Tyler, 30 years her senior, in 1844. “I very well know, every eye is upon me, my dear mother, and I will behave accordingly,” she wrote. In her painted portrait, she is dressed like a princess in a pale pink silk and satin gown with a pearl necklace and diamond tiara headband.

Tyler supported slavery and made a public argument that Americans treated their slaves well. “It was interesting for me to think about a woman like Julia Tyler and the way that a portrait like this helped to create an identity for her and empower her,” Shaw says, “to in that moment speak to these differences and these changes and the ways that the roles of first ladies have mirrored the lives of American women.”

Many of the women faced tremendous challenges and have fascinating biographies, and Shaw includes telling details in each description, some not previously highlighted. “I felt I was able to articulate the importance of studying race and its historical impact on the country from that vantage point for first ladies,” she says.

Shaw chose to include a print that reflects Martha Washington’s lesser-known history. Martha, who had children in her first marriage and was widowed, is pictured with her second husband, George Washington, and two of her grandchildren, including George Washington “Wash” Custis. As an adult, the description explains, Wash had a daughter with an enslaved house servant. And Martha Washington owned slaves herself, including her own half-sister, Ann Dandridge.

“Martha Washington had a Black sister and Black great-grandchildren, which has not been part of her narrative,” Shaw says. “I was thinking about how African Americans had been a part of these first families.”

Mary Lincoln is known for her focus on fashion, and Keckley became an important friend and ally, which is why including the elaborate pink capelet was important to Shaw. “I wanted to talk about how race and gender shaped these women’s lives, and the bonds that they had with the women who served and facilitated them,” she says. “I was able to weave that in in different ways.”

In addition to Lincoln’s capelet, Shaw included only three outfits, displayed on mannequins, keeping in mind that the National Museum of American History has a permanent exhibit, The First Ladies, which features more than two dozen gowns.

“I felt it was important to bring these women’s bodies into the space,” Shaw says. “I chose garments that hadn’t been seen in Washington, D.C., since they were worn.”

One is the dress Michelle Obama wore in her Portrait Gallery painting, which became an iconic garment adopted as an empowering costume by young girls and women of color, Shaw says, noting that it features a striking pattern drawn from African American quilting traditions.

“I thought it was important to bring that dress to the public to see how simple and elegant it is, made out of cotton poplin that everybody has in their closet. It’s really a maxi dress, but in the portrait it looks like a ballgown,” Shaw says. “It shows the way portraiture can change perceptions about people.”

Original article can be found HERE.